Child Brides Disgrace!

Nigeria's child brides: 'I thought being in labour would never end'

Though child marriage is prohibited under Nigerian law,

a toxic blend of routine and religion continues to ruin

young lives

a toxic blend of routine and religion continues to ruin

young lives

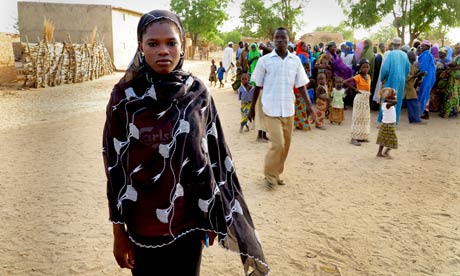

Nigerian child bride

activist Zainab Oussman, 16,

in Kwassaw village. At 14, she refused to marry,

instead staying in school.

in Kwassaw village. At 14, she refused to marry,

instead staying in school.

Ibrahim Kanuma winces as he recalls the moment

a 63-year-old man asked him for his teenage

daughter's hand in marriage. The proposal was not

unusual in north-western Nigeria's remote, dust-blown

state of Zamfara, but he considered the suitor too old

for his only daughter, Zainab, 13.

"Even if he had been aged up to 50 – OK. But that old,

he'll soon die and leave her lonely," says the civil

servant in his peeling office in Gusau, the state

capital. To protect his school-aged child from the

crushing stigma of widowhood, Kanuma instead

gave his blessing to a union with a "reasonably aged"

colleague – in his 40s – even though such a betrothal

is illegal.

For Kanuma and many others in northern Nigeria,

the recent outcry over child marriage is puzzling.

Zainab's marriage is prohibited under Nigeria's

Child Rights Act, which bans marriage or betrothal

before the age of 18. But federal laws compete with

age-old customs, as well as a decade of state-level

sharia law in Muslim states.

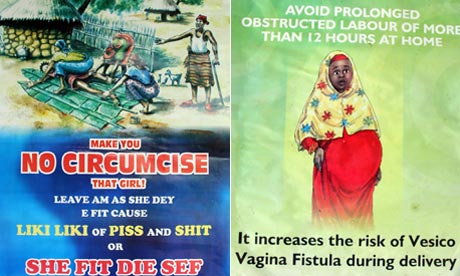

Warning posters about female circumcision and

fistulas.

"I wouldn't force my daughter to marry somebody she

doesn't like, but as soon as a girl is of age

[starts menstruating], she should be married,"

Kanuma says.

Four of the 10 countries with the highest rates of child

marriage are in west Africa's Sahel and Sahara belt. In

the years when rains or crops fail, so-called "drought brides"

– who bring in a dowry while being one fewer mouth to feed

– push numbers up dramatically.

But the practice came under scrutiny in July, when

legislators tried to scrap a constitutional clause that states

citizenship can be renounced by anyone over 18 or a married

woman, apparently implying womencan be married under 18.

The obscure ruling will have little direct impact on the one

in four rural northern Nigerian girls married off before they

turn 15, but it reveals

prevailing attitudes in a nation with acute gender disparity.

A successful vote was later derailed by senator Ahmed Yerima,

who in 2010 married a 13-year-old from Egypt. A former

Zamfara governor who

introduced a rigidly enforced version of sharia law in the north

in 2000, Yerima argued that a married girl was considered an

adult under certain interpretations of Islamic law. That prompted

outrage. "Does it then follow that the married girl who is

below 18, at election time, would be permitted to vote?" says

Maryam Uwais, a lawyer and child rights advocate in the

northern capital of Kano.

Other grassroot Muslim activists, however, fear the oxygen

of negative publicity trailing the high-profile Yerima, coming

most vocally from non-Muslims, could trigger a backlash among

conservative, rural Muslims. This would threaten painstaking

progress towards modernisation over the past decade.

In the week headlines erupted over Yerima, Aisha, nine, was

quietly rushed through the corridors of Zamfara's Faridat Yakubu

general hospital. Its cheerful cornflower blue walls belie stories of

the hidden horrors of early marriage. Aisha does not have the

words for what happened to her on her wedding night. Her husband,

she says, did something "painful from behind".

Nearby, Halima was on her third visit in three years. "I like it here.

It is the only time I ever see a television," she says. Just shy of 13,

the newlywed came under pressure to demonstrate her fertility.

"I thought [being in labour] would never end," she adds softly.

In the tradition of the rural Hausa people of the north, women are

expected to give birth at home. Crying out while in labour is seen as

a sign of weakness. But after three days close to death in her village,

Halima begged to be taken to a hospital. By the time her relatives

had scraped together enough to ferry her to the state capital, it was

too late.

The baby had died.

The prolonged labour left Halima with a fistula, which causes

uncontrolled urination or defecation. "Fistulas can happen to anyone,

but are most common among young women whose pelvises aren't at

full capacity to accommodate the passage of a child," says Dr Mutia,

one of two practising fistula surgeons in Zamfara.

Despite the obvious link, he is reluctant to blame child marriage for

Nigeria having the highest global rate of fistula. "The problem is not

early marriage. It is giving birth at home," he says.

Small victories

There have been small victories in reversing the ripple effects ofearly and forced marriage, defined as forms of modern-day slavery

by the International Labour Organisation.

Fifteen years ago, Zamfara's statistics director, Lubabatu Ammani,

carried out a census to record the number of girls attending

secondary school in the state. The results were shocking: fewer than

4,000 girls were enrolled out of a population of 3.2 million.

"It was a combination of dropouts, early marriage and religious

misinterpretations," explained Ammani, who proposed creating a

female education board to help remedy the problem. "We asked all

the local emirs and found the main problem was that parents didn't

want girls who had hit puberty to be in co-ed schools."

Female enrolment in Zamfara is at its highest since independence

five decades ago, with 22,000 secondary school students. On most

days, Ammani visits wavering parents to encourage them to keep

their daughters in school.

Ammani welcomes the reawakened debate on child marriage but

warns of its limits: "The fact is, a lot of people [here], when they

hear the campaigning is by people from a different tradition or

religion, they won't agree with it."

Others are more blunt. Haliru Andi, who served as Yerima's top

aide while he led the call for sharia, bristles at the idea of interference

with his faith. "How I even use the toilet, how I share my time with my

family – everything is contained in my religion," he says in his

Persian-carpeted living room. "How, then, can I take instructions from

anybody who does not have a deep understanding of Islam?"

Cultural norms further muddy the issue. Posters outside Mutia's office

exhort against another disturbing practice related to child marriage.

In one,a woman is being forcibly restrained on a woven palm-frond mat.

An assistant grabs her legs; another sits on her chest, and yet another

reaches between her legs with a razor blade.

The scene shows a common recourse when a child bride refuses to sleep

with her husband, prompting her parents or in-laws to drag her to the

wanzan, or traditional barber. "This traditional barber, he doesn't

understand anatomy. He thinks there's something obstructing the girl

down there, and that's whyshe fears her husband. So anything he sees,

he will just use his knife to cut it,"

Mutia explains. "They think they are helping."

None of the northern-based grassroots Muslim activists the Guardian

interviewedwanted to go on the record about child marriage – reflecting,

says one activist, the difficulties women face "going against the grain".

The storm of Twitter and online commentary has translated into a

handful of protests in the more liberal south, which is predominantly

Christian but also home to millions of Muslims.

In the tiny village of Rigasa, flanked by baobab trees and fields of millet,

Nafisa, 14, draws letters in the powdered maize she grinds every morning

for herself and her in-laws. A-B-C-D, she writes. It is all she remembers.

"My husband gets angry any time I asked him if I can take up my schooling

again, so I stopped asking. But my heart is in school," she says.

Labels: Abject ignorance, Abject poverty, Banana Republic, Popular culture

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home